Reviews

The Evolution of Journalism: Past, Present, and Future

Journalism is a phenomenon – indeed, an institution – that has helped form the bedrock of modern society. From the handwritten news pamphlets of Greek or Egyptian antiquity, through Renaissance-era mass-printed newspapers, to the breathless minute-by-minute television and internet media coverage we are inundated with today, journalism in some form or another has been an integral part of human society since ancient times. People from all walks of life have depended on some form of news media to learn about the world around them for ages beyond counting, and however the practice of journalism may morph and evolve, as long as one can obtain an online journalism degree, surely it will be with us for some time.

Our Roots

No matter how much things have changed, when we think of journalism today, we don’t exclude the medium used by what many would likely consider the original journalists: the newspaper. Even our most modern forms of digital written media still derive inspiration from the format, style, and content of the earliest newspapers. The invention of the printing press doubtless represents the biggest turning point in mass distribution of information, and is often regarded as the beginning of the Enlightenment period, which heralded the first explosion in literacy rates in Europe, and subsequently the rest of the world over the following centuries. Surely it’s no coincidence that the Enlightenment also gave birth to influential thinkers like Voltaire, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Adam Smith, whose ideas influenced the establishment of modern forms of government and institutions, freedom of speech being not the least amongst them, being itself a core tenant of our modern conceptions of journalism.

Surely we shouldn’t be so quick to exclude older, perhaps less technologically refined, yet equally important – if not more so – early bringers of news. If we assert that the primary function of a journalist is to democratize access to information, we could speculate that someone as early as Martin Luther could be seen to fill such a role – his translation of the Bible from Latin into German and English enabled entire classes and regions of people to have direct access to the written Bible, thwarting the intellectual and religious stranglehold held by the priest caste on medieval Europeans – arguably one of the seminal forces of the Renaissance.

We could go back even further and point to town criers and early bulletins in ancient Rome as early drivers and influences on the culturally embedded, inter-millennial memes that help enable the freedom of access to information we enjoy today. It might be a stretch to call Virgil and Horace journalists rather than Augustan propagandists, but to deny their influence on the modern concept of journalism – of public storytelling and information sharing – would be more than selective: it would be dishonest.

Their Branches

But perhaps such influences – and the specter of their political entanglements – have cast a greater shadow on our current conceptions of what constitutes journalism than we might care to acknowledge. Surely we would be better served as a society by more Walter Kronkites, and fewer Rachel Maddows or Tucker Carlsons. Unlike news media of yesteryear, which were bought and sold purely as sources of information, and thrived or failed on the accuracy and usefulness of their reporting, our current news paradigms are supported by advertising rather than straightforward transactions.

We’ve become so accustomed to news media as a “free” commodity, that we seem to have forgotten that everything has its price. And the real price of ad supported media is the impact it has on the content: the incentive to sell more ads, more impressions, and more clicks has driven journalism away from truth, and into the arms of attention – journalistic publications make money not by being reliable, reputable sources of information, but rather by generating the most inflammatory, eye-catching headlines possible, and keeping readers riveted with gripping, divisive narratives, scrolling as far as possible down the rabbit hole of social and political extremism as is necessary to generate the maximum number of ad impressions – or even a single click that leads to a purchase.

And alas, just as in ancient times, the stories that best capture people’s attention and enliven their imaginations – for better or worse – is politics. Surely it’s no surprise that the lowest common denominator for attention between humans as a species would be the events that affect the most of us: the machinations of our governments, and those of other governments that might have some impact on our own safety or ability to flourish. Does anyone sell more ads than Donald Trump? Perhaps Valdimir Putin. It should come as no surprise – the very first printed newspaper carried political news.

It’s an informational environment that showcases trends which one might assume could be ameliorated by a tool as useful for the dissemination of information as the internet. After all, if Martin Luther’s accessible translations and the mass distribution offered by the printing press helped bring wisdom and insight to more people, shouldn’t further technological progress amplify those trends?

Perhaps. It can’t be ignored that social media outlets like X, YouTube, and Facebook have certainly contributed to the democratization of information distribution. Now anyone can be a journalist – surely increased competition resulting from lower barriers to entry would incentivize better behavior from larger journalistic outlets? It may, indeed, be the only check we have on the decline of these vital institutions – they can only fall so far without losing relevance entirely.

The Fruit of Temptation

And yet even our noble citizen journalists are faced with a conundrum of incentives. Journalists of yesteryear would have clamored over one another for the analytics tools afforded to modern social media influencers: granular data about the demographic characteristics of their viewership, how many views each post gets, how long each viewer’s attention is captured by a video: these are tools that even stalwart institutions like the New York Times would have paid millions for just 20 years ago, and are now free for even the lowliest YouTuber.

But at what cost? If an aspiring “journalist” on YouTube can see exactly which of their opinions garners the most approval – or at least the most attention – from their viewership, what’s holding them back from throwing their values to the wind and simply amplifying those signals in their content, succumbing fully to ideological capture by algorithmic circulation in the process? Might their own views even be altered, warped by the perverse incentives at play for sustaining not only the attention of their current audience, but also the fickle algorithms that keep their content flowing to fresh eyeballs?

Only time will tell if other stronger incentives will emerge to rescue our informational environment from the dark night of the soul it finds itself in.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCargo plane plunges into sea at Hong Kong airport; 2 killed

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoMexico reports new human case of H5 bird flu

-

US News5 days ago

US News5 days agoUnwarned tornado suspected in Fort Worth as storms cause damage and power outages

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoU.S. Navy helicopter and fighter jet crash in South China Sea; all crew rescued

-

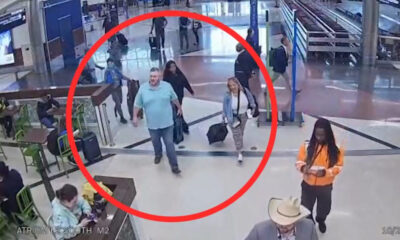

Legal1 week ago

Legal1 week agoMan armed with AR-15 arrested after threats to ‘shoot up’ Atlanta airport

-

Legal4 days ago

Legal4 days agoMultiple injured in shooting at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoMagnitude 5.0 earthquake rattles Dominican Republic

-

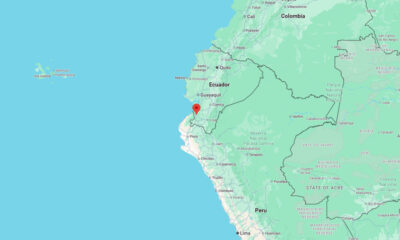

World1 week ago

World1 week agoMagnitude 6.1 earthquake strikes Ecuador–Peru border region