Reviews

Future Demographics and Their Economic Consequences

Demographic change is one of the most powerful forces shaping the global economy. This article will explore how shifting population structures, aging societies, migration, and youth bulges affect growth, innovation, and stability.

Understanding Demographic Shifts in Context

When economists try to anticipate long-term changes, they often ask not just what are futures in financial markets, but also what demographic “futures” look like. Futures contracts allow traders to lock in expectations, and in much the same way, governments and businesses try to anticipate population trends decades ahead. These forecasts are not speculative games, they are the basis for policies on pensions, health care, housing, and labor markets. The difference is that demographic projections tend to be more predictable than financial markets, but their consequences are often harder to reverse.

Population growth patterns, fertility rates, and mortality rates all combine to create demographic momentum. Once a country has an aging population or a youth surge, it cannot quickly change the shape of its demographic pyramid. These realities form the backdrop for economic planning.

The Aging of Developed Economies

One of the most striking global trends is the aging of populations in developed economies. Countries such as Japan, Italy, and Germany already face shrinking workforces and rising dependency ratios. This means fewer workers are supporting more retirees, straining social security systems and health care budgets.

Economic consequences include slower growth, higher taxes, and increased government borrowing. Older populations also tend to be more risk-averse, which can reduce entrepreneurial activity and the appetite for innovation. At the same time, industries that cater to seniors, such as health care, pharmaceuticals, and leisure services, see strong growth opportunities.

For policymakers, the challenge is to balance fiscal sustainability with providing for an aging citizenry. Raising retirement ages, encouraging immigration, and boosting labor force participation among women are some of the tools often discussed.

Youth Bulges in Emerging Markets

In contrast, many developing nations are experiencing a demographic youth bulge. Large populations of young people can be either an asset or a liability, depending on how well economies absorb them into productive employment. Countries such as Nigeria, Pakistan, and parts of the Middle East have rapidly growing youth populations.

If education systems, job creation, and infrastructure keep pace, these young people can drive decades of economic growth, a so-called demographic dividend. However, if opportunities are lacking, high youth unemployment can fuel social unrest, migration pressures, and instability.

Investors and global businesses are watching these regions closely. The consumer base in Africa and South Asia will expand dramatically in the coming decades, offering huge markets for goods, services, and technology. But the risks of volatility remain real if growth does not match expectations.

Migration as a Balancing Force

Migration is another powerful demographic factor with direct economic effects. Many developed countries rely on migrant workers to fill labor shortages in health care, agriculture, and technology. Immigration can offset the decline in working-age populations, bring in new skills, and stimulate innovation.

However, migration also raises political and cultural challenges. Debates around immigration policy often pit economic needs against social cohesion concerns. Countries that strike a balanced approach can benefit from the dynamism of diverse workforces while maintaining stability.

On a global scale, migration helps redistribute labor from surplus regions to shortage regions, somewhat balancing the demographic map. Remittances sent home by migrant workers also represent a vital source of income for many developing countries.

Urbanization and Shifts in Economic Power

Demographic change is not only about age structures but also about where people live. Urbanization continues at a rapid pace, especially in Asia and Africa. By 2050, more than two-thirds of the world’s population is expected to live in cities.

Urban concentration creates both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, cities drive innovation, efficiency, and economic growth by concentrating talent and resources. On the other hand, rapid urbanization strains infrastructure, housing, and public services. Policymakers must manage these transitions carefully to avoid creating megacities plagued by inequality and environmental stress.

Urban growth also shifts economic power. Cities like Lagos, Mumbai, and Jakarta are poised to play roles on the global stage comparable to those of New York, London, or Tokyo. For global investors, understanding these urban centers is as critical as tracking national GDP figures.

Technological Implications of Demographic Change

Technology interacts deeply with demographics. Automation and artificial intelligence, for example, can compensate for shrinking workforces in aging societies. Robots and digital tools may help Japan maintain productivity despite a declining labor pool.

At the same time, technology creates jobs in new sectors that may align well with youthful populations in developing countries. E-commerce, fintech, renewable energy, and digital services can provide employment paths for millions of young people. The challenge is ensuring that education and training systems prepare workers for these new opportunities.

Conclusion

Future demographics are not just abstract statistics, they are powerful drivers of economic outcomes. Aging societies face slower growth and fiscal strain, while youthful societies hold both promise and risk depending on how opportunities unfold. Migration, urbanization, and technology interact with these forces to create a complex global picture.

-

Legal6 days ago

Legal6 days agoMichigan man JD Vance sentenced to 2 years for threatening Trump and JD Vance

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoU.S. to designate Maduro-linked Cartel de los Soles as terrorist organization

-

Health7 days ago

Health7 days agoCambodia reports fatal H5N1 bird flu case in 22-year-old man

-

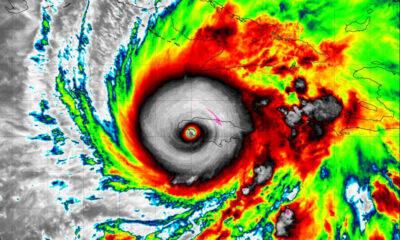

World4 days ago

World4 days agoHurricane Melissa registered 252 mph wind gust, breaking global record

-

Legal4 days ago

Legal4 days agoWoman in critical condition after being set on fire on Chicago train

-

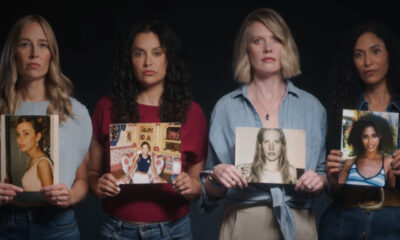

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoEpstein survivors release PSA calling on Congress to release all files

-

Legal4 days ago

Legal4 days ago1 dead, 2 injured in shooting at Dallas Walmart parking lot

-

Legal3 days ago

Legal3 days agoSuspect in San Diego stabbing shot by authorities after fleeing into Mexico